One of the worlds most ancient traditional crafts – the processing of flax, hemp and nettle bast fibres – has been placed on both the endangered and resurgent list by the heritage crafts charity (UK), 2025.

Flax – A golden thread intricately weaving people, place, time and landscapes together with a deeply rooted heritage story.

“…..and it was as if a thousand voices echoed the words………. but the little invisible beings said, “the song is never ended; the most beautiful is yet to come.”

~ Hans Christian Anderson ‘The flax‘. (1849)

Some time between c.4000 BC and c.3900 BC (E. Neolithic), on the coast of continental Europe (Sheridan & Whittle, 2023,p.170), communities of farmers, navigators and artisans embarked onto their expertly crafted boats, preparing to sail across the channel to the Islands which today we call Britain and Ireland. Each vessel readied, laden with the vital tools and materials necessary to farm new and uncultivated lands successfully and to sustain life.

Amongst these carefully chosen and precious resources were tiny brown, shiny, oval-shaped seeds, which when sown into the correct soils and environment, and nurtured with knowledgable hands, grow into tall and vibrant green stems, and for only a day, just prior to their harvest time, they showcase their bloom with an array of delicate blue flowers.

These seeds, known by their scientific name, Linum usitatissimum – popularly known as Flax, are one of the worlds oldest cultivars. With it’s enduringly strong fibres and versatile nature, flax was a practical crop to include in their cargo, and it has remained a consistent source of subsistence ever since – whether it’s been grown for it’s oil, dietary & medicinal uses, or for textiles, by processing and weaving into linen. The growing process, from sowing the seeds to harvesting, takes approximately 100 days for the flax to reach it’s full maturity.

The treatment and processing of flax is a scientific endeavour, with several parts to the process. It is a heritage craft which has been traditionally passed on throughout the generations, through oral traditions, folklore, and practical teaching. Vital ingredients needed for success if growing on a large scale: knowledge, skill, manpower, and patience – preparing the ground and soil and then sowing the flax seed, weeding and nurturing throughout the growing process, then harvesting the flax, pulling the plant from the ground – roots included. The next stages are crucial if the intent is to harvest the fibres to create linen, and some of these stages are represented within the archaeological record. Below is the story of the introduction of flax, evidencing these traditional skills being passed down through the generations using the evidence within the archaeological record to illustrate the process…..

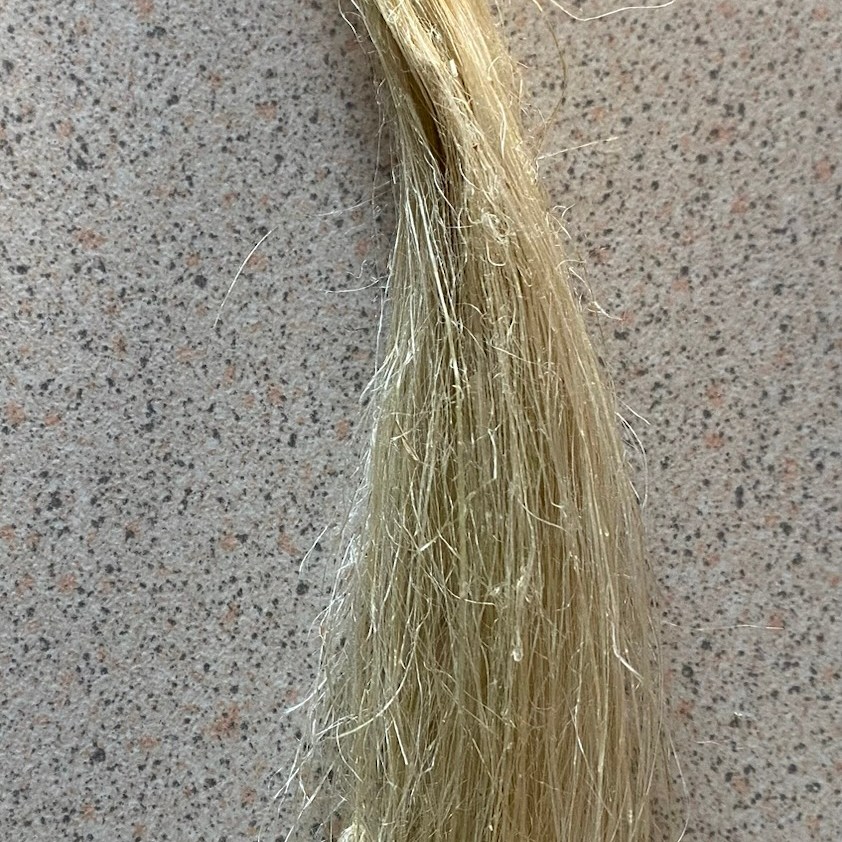

Images above: My results from growing and processing flax at home – part of a flax project led by NOSAS in 2021, McKittrick, A

Flax began its journey as a wild plant named pale flax (Sc. Linum Bienne), and is believed to have been among some of the earliest crops to be domesticated by humans, some time between c.9th-8th Millenniums BC in the fertile crescent, where agriculture was first developed (Bar-Yosef, 2020:9-11). The oldest surviving dated flax tool artefact comes from assemblages associated with Wadi Murabba ‘At in the Judean desert, and consists of a 10 pronged, long comb-like wooden structure with domesticated flax intertwined in a tightly woven, crafted manner (Schick et al 1995). (The comb itself – whilst much older and made from wood – is remarkably similar in design to bone weaving combs, such as the ones in the National Museum of Scotland’s collections which you can view here). The domestication of flax is a key point in human evolution, and the presence of cultivated flax (Linum usitatissimum) in Neolithic archaeological contexts may be considered as a worthy indicator of the successful adoption of an agrarian lifestyle.

Sowing, growing and harvest:

In Europe, the presence of cultivated Flax has been found in archaeological contexts dating to the 6th millennium BC (Karg et al, 2017:31), with later evidence of sophisticated production and processing techniques evidenced in the Alpine regions of the Upper Swabia and Lake Constance Neolithic wetland settlements, dating c.4000-2500 BC (Maier & Schlichtherle 2011:571). It is exceptionally rare to uncover such a wealth of evidence, especially dating to the Neolithic period; naturally, organic remains like flax and wood decompose quickly in most conditions, dissolving back into the earth. The waterlogged contexts at both Lake Constance and Upper Swabia provided ideal preservation habitats for the survival of flax and related processing tools, providing exceptionally strong evidence of it’s adoption in Europe and exhibiting the processing techniques in this region.

For Britain and Ireland, the introduction of flax by those first farmers sailing from the continent would be the beginning of a long and impactful heritage story. The earliest radiocarbon dates (C14) for Linum usitatissimum in Britain come from two intriguing Neolithic sites within settlement structures at Balbridie and Lismore fields. The first, Balbridie (Fairweather & Ralston, 1993, Hedges et al, 1990:216-17), sits on the southern bank of the river Dee, Aberdeenshire, in close proximity to a notable mesolithic site on the Northern bank of the River Dee, and slightly east of Balbridie. The second, Lismore fields (Jones & Bogaard, 2017, Bayliss et al, 2013:109), is located on the Southern bank of the river Wye. It is the location of one of the best preserved neolithic structures in Britain, and was a busy settlement during it’s lifetime. Both sites have been interpreted to have played significant roles in the early adoption of agriculture, and both have flax well represented at their sites, although the nature of the purpose of flax cultivation during that time is currently uncertain. Flax growing on a large scale would have required a great deal of management – as it is pulled from the ground with it’s roots intact, this makes it an exhaustive crop, leaving the soil without vital nutrients.

Due to the lack of evidence of fibre processing and associated tools during these early stages of its introduction, it could be assumed that flax was initially grown for its oil rather than for fibre. There are however, two intriguing pottery discoveries of Neolithic date which have imprints of woven fabrics impressed upon them, providing some food for thought – one from Dumfries & Galloway and another more recent discovery from Ness of Brodgar (Ness of Brodgar project blog, 2020). Whilst the imprints don’t clarify which textile material the fabric was made from, or the type of garment which left it’s distinctive impression in the clay, it does confirm that textile weaving was being practiced at this time, and that the products created were accessible to these communities in Orkney.

Drying, rippling and retting:

Evidence for the processing of flax for its fibre becomes more apparent within Bronze age horizons. Excavations at Reading business park (Moore & Jennings et al, 1992:122) uncovered retting pit features which served as an important element of the processing of flax to fibre for the Bronze age community which lived there. The inhabitants of this area, after harvesting, drying and collecting the seed pods (rippling), would have taken the flax to these retting pits and anchored them down in the stagnant waters. This vital part of the process is where the chemical reactions between the standing water and plant separates the fibres from the stem. Whilst it’s a particularly dirty step in the process, and the pungent smell of the retting pits would have filled the air around them, this method of water retting accelerates the process at a much quicker rate than the alternative of dew retting. Water retting takes around 14 days +/-, however it is possible to under ret or over ret the flax, so judging its readiness correctly is crucial to ensure that the fibre is usable.

Breaking, Scutching, Hackling:

Must Farm, another Bronze age site, and one of exceptional preservation, bestowed some lovely evidence of flax processing, with tidy fold and turn bundles of flax fibre uncovered in an area of the burned down settlement (Harris & Gleba, 2024:461-534). These bundles would have been the result of successful flax processing – fully retted and dried out, the straw-like rigid woody stalks broken away, separating from the enclosed fibre, before then being combed through and revealing the long, strong fibres – the result of a long and laborious process. The spatial distribution of these flax bundles is interesting, excavated from a small space in structure 1, suggesting a storage space for these textiles (Harris & Gleba, 2024:487-489). Must farm is a beautifully preserved Bronze age site, and provides a wonderful example of a space where the sharing of skills and knowledge, and the continuation of passing down of this traditional craft may have taken place.

Spinning and weaving:

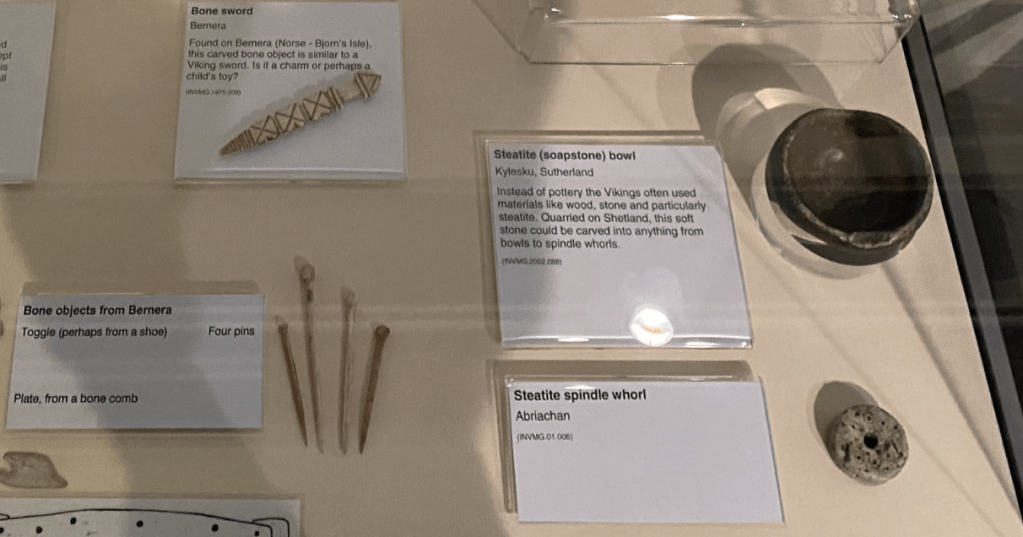

The next step in the process is to then spin – with the raw fibres spread around a distaff, and then either spun into a tight thread using a drop spindle with a spindle whorl weight at the end, or on a more technologically sophisticated spindle wheel. Prehistoric evidence for these tools are rare in Britain and Ireland, however whorls can be a more common find depending on their raw material and context. The Viking-age Spindle whorl in the image below, made from Steatite provides another example of a shared cultural heritage through textile practices – whether it was used to spin flax or other material like wool or hemp, spinning natural fibres was a well established practice.

Viking-age Spindle whorl made of Steatite, discovered in Abriachan, Scotland. Can be viewed at Inverness Museum & Art Gallery.

McKittrick, A, 2022.

Once the raw fibre has been spun into thread, it can then be prepared to be worked, and transformed into linen through the weaving process, which involves skilfully and methodically interlacing multiple strands of horizontal (weft) and vertical (warp) threads tightly together to form a cloth. The tools used to achieve this result are looms and were made in varying types. For the Picts, they may have used either a warp weighted vertical loom, which was similar to the Anglo-Saxon’s, or a two beam vertical loom, similar to their contemporaries in Ireland (Stirling & Milek, 2015).

The Brough of Birsay in Orkney has been interpreted as a site of high status, and the textile assembles such as whorls and loom weights are of differing weights and sizes (Stirling & Milek, 2015). These varying types of loom weights and whorls could have been used to create diverse textures (i.e. heavier whorl, spins a tighter thread) and the various loom weights would aid differing styles of weave during the weaving process. As siggested by Stirling & Milek (2015), this diverse range of tools suggests the possibility that the brough of Birsay was an artisanal site, creating high quality textile wares. As the structure of looms were likely made from wood, an organic material, the main body of a loom is lost to the acidic soils.

By the medieval period onwards, it is clear from historical records that flax for fibre was a staple material. In the early 1500’s the state ruled that for every 60 acres of arable ploughspace, 1 rood (a medieval measurement- similar to c.1/4 acre), should be kept for the purpose of growing flax or hemp – the linen produced used for clothing and garments, bedding, canvas, upholstery, tapestries, sails and ropes (Hayward, :69-70). During the Industrial revolution there was an acceleration of flax-related work, with purpose built factories and textile mills being built across Britain and Ireland, with new machine technologies used to produce linen quickly and efficiently to meet commercial demands (Rynne, 2022:189-201). These buildings changed the landscape of many rural areas and towns across Britain and Ireland, and the remnants of this industry and it’s associated buildings can still be seen today, whether as abandoned sites, or reused and repurposed buildings.

Generally, traditions are often at the mercy of new sophisticated technologies, either through shifts within the social & cultural structures of life that fosters a tradition, or by rendering that tradition obsolete. However, flax fibre is unparalleled – it’s composition is sturdy, strong, durable and high quality, with no other fibre, natural or synthetic, comparable to its characteristic qualities. It’s not the linen itself that is classed as endangered – it is the unique traditional skills of the processing stage which have been reverentially passed down through millennia, which are deemed at risk. The survival of traditions, wether tangible or intangible, depends greatly on the continuation, sharing and practicing of heritable knowledge and skills, and the drive of each generation to sustain those traditions. I certainly wouldn’t have managed to grow and process my own humble little patch of flax without the guidance from knowledgable members of my local archaeology group and online resources.

Flax and linen can be seen in varying forms and contexts, evidenced through archaeology, material culture such as tools or products, and it is modestly present in some of our most well known material culture too. Keep an eye out next time you visit a heritage site or museum!

Growing & processing flax can teach much more than traditional skills – it offers a much deeper appreciation for the craft, the end product (linen) & the people over time who have played a part in its history and survival. A powerful fibre which has played an important role for thousands of years! It’s a worthwhile project to try out!

REFERENCES:

*Anderson, H.C (1915)*’The Flax‘, In ‘The project Gutenberg e-book of Hans Andersons fairy tales, 2nd series‘, J. H. Stickney (Ed), (2010), Ginn & Company, Boston. Accessed here May, 2025

Bar-Yosef, O (2020), ‘The neolithic revolution in the fertile crescent and the origins of fibre technology‘ in ‘The competition of fibres: Early textile production in Western Asia, South-East and central Europe (10000-500BC), Scheir, W & Pollock, S (Eds), Oxbow books, Oxford, Ch.2, pp.5-15. accessed here May, 2025.

Bayliss, A et al (2013), ‘Radiocarbon dates from samples funded by English heritage between 1988 and 1993‘, English Heritage, Swindon. Accessed here May 2025.

Council for British Archaeology (2012) ‘Archaeological Site Index to Radiocarbon Dates from Great Britain and Ireland [data-set]’. York: Archaeology Data Service [distributor], accessed here May, 2025.

Fairweather, A & Ralston, I (1993) ‘The Neolithic timber hall at Balbridie, Grampian region, Scotland: The building, the date and the plant macrofossils‘, in Antiquity Vol.67:255, pp.313-323, Accessed here May, 2025.

Harris, S & Gleba, M (2024) ‘ Fibres and fabrics‘ In ‘Must farm pile dwelling settlement‘ Vol.2 Specialists reports, Ballantyne, R et al (Eds), McDonald institute for archaeological research, Cambridge CH.12 pp.461-534. Accessed here May, 2025.

Hayward, M (2009) ‘Rich apparel: Clothing and the law in Henry VIII’s England’, Ashgate publishing company, Surrey. pp.69-70

Hedges, R et al (1990), ‘Radiocarbon dates from the Oxford AMS system: Archaeometry datelist 11‘ In ‘Archaeometry Vol.32:2‘, pp.216-217 University of Oxford. Accessed here May, 2025.

Jones, G.E. & Bogaard, A. (2017) ‘Integration of cereal cultivation and animal husbandry in the British Neolithic: the evidence of charred plant remains from timber buildings at Lismore Fields‘, in ‘Economic Zooarchaeology: Studies in Hunting, Herding and Early Agriculture‘. Rowley-Conwy, et al (Eds.) , Oxford , pp.221-226 Accessed here May, 2025.

Karg, S et al (2017), ‘Discussing flax domestication in Europe using biometric measurements on recent and archaeological flax seeds – a pilot study‘, in ‘First textiles: The begginings of textile manufacture in Europe and the Mediterreanean‘, Siennicka, M et al (Eds), Oxbow, Oxford, Ch.3 pp. 31-38. Accessed here May, 2025.

Maier, U & Schlichtherle, H (2011), ‘Flax cultivation and textile production in Neolithic wetland settlements on Lake Constance and Upper Swabia (S/W Germany)’, in Vegetation history and archaeobotany vol.20, Springer, pp.567-578. accessed here May, 2025.

Moore, J & Jennings, D (1993) ‘Reading business park: A Bronxe age landscape‘ In ‘Thames valley landscapes: The Kennet valley’, Vol.1, Oxbow books, Oxford, p.122. Accessed here May, 2025.

Ness of Brodgar project blog (2020), ‘Evidence of woven textiles confirmed at Ness‘, Accessed here May, 2025.

Rynne, C (2022) ‘The Linen and wool industries in Britain and Ireland‘, In: ‘The Oxford handbook of industrial archaeology‘, Casella, E et al, Oxford University press, Oxford. Accessed here May, 2025

Sheridan, A & Whittle, A, (2023), ‘Ancient DNA and modelling the Mesolithic-Neolithic transition in Britain and Ireland’ in ‘Ancient DNA and the European Neolithic: relations and descent‘, Whittle, A et al (Eds), Oxbow books, Oxford, Ch.12 p.170.

Shick, T et al (1995) ‘A 10,000 year old comb from Wadi Murabba ‘At in the Judean desert‘, Accessed here May, 2025

Stirling, L & Milek, K (2015) ‘Woven cultures: New insights into Pictish and Viking cultural contactusing the impliments of textile production‘, In Medieval archaeology, Vol.59:1. pp.47-72, Accessed here May 2025

https://www.heritagecrafts.org.uk/categories-of-risk/

Useful resources, links, information…..:

Seamus Heany’s ‘death of a naturalist’ here

*Heritage crafts website link to endagered list here, Accessed May, 2025

*Sally pointer heritage educator – invaluable YouTube site: https://youtu.be/QBnPuzY1GUQ?feature=shared

*Viking steatite spindle whorl can be viewed at Inverness Museum & Art Gallery, link here. Accessed May, 2025.

Sheridan, A (2010) ‘The Neolithization of Britain and Ireland: The ‘big picture’‘ In ‘Landscapes of transition’, Finlayson, B & Warren, G (Eds), Oxbow books, Oxford, Ch.9, pp.89-105, Accessed here May 2025.

Bo Ejstrud et al (2011) ‘From flax to linen: Experiments with flax at Rube Viking centre‘, Maritime archaeology programme & University of Southern Denmark, Esbjerg, accessed here May 2025. *A useful step-by-step project – growing, processing, spinning and weaving flax to linen, and a guide to make a replica Viking-age garment*.

*Below: An Informative Youtube recording of NOSAS member Anne Coombs’ presentation sharing the story of the history, processing and archaeology of Flax in the Highlands* Accessed May 2025.

Flaxland website: https://www.flaxland.co.uk/ Accessed May, 2025

*Facebook ‘Flax to linen’ community group: https://www.facebook.com/groups/374949366027023/

*Weaving combs on the NMS website can be viewed here, Accessed May 2025.